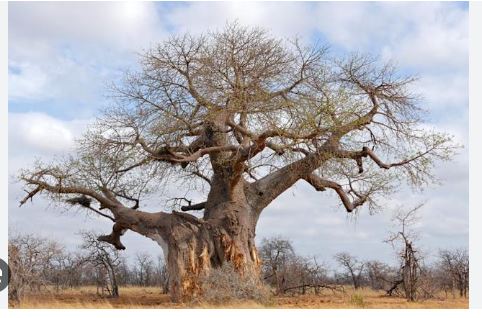

Baobab trees, often called the “Tree of Life,” are iconic giants of tropical landscapes, revered for their massive, water-storing trunks and extraordinary longevity. Native to Africa, Madagascar, Australia, and parts of the Arabian Peninsula, these deciduous trees thrive in arid savannas and dry forests, supporting ecosystems with their fruit, leaves, and hollow trunks. Their cultural significance spans folklore, sacred sites, and modern superfood markets, with every part used for food, medicine, and materials. Their swollen trunks and sparse, umbrella-like canopies create a striking silhouette, earning them a place in art and legend.

Growing 20–100 feet tall, baobab trees can live over 2,000 years, with trunks reaching 30 feet in diameter, storing thousands of gallons of water to survive droughts. Their palmately compound leaves emerge in the rainy season, while white or yellow nocturnal flowers, pollinated by bats or lemurs, produce nutrient-rich fruit. Thriving in USDA zones 10b–12, they prefer well-drained, sandy soils and full sun, tolerating extreme heat but not frost. Their deep taproots and fire-resistant bark ensure resilience in harsh climates.

Cultivating baobab trees requires patience, as they take 10–20 years to fruit, though grafted saplings may produce sooner. Seeds need scarification or acid treatment to germinate, and young trees demand minimal watering to avoid rot. Harvest fruit when shells harden, drying the pulp for storage. In non-tropical zones, they can be grown as bonsai, adding exotic flair to patios. Their slow growth and dioecious nature (male and female flowers on separate trees for some species) make pollination planning essential.

Baobab trees are ecological powerhouses, stabilizing soils, sequestering carbon, and providing habitat for birds, bats, and insects. Their fruit pulp, packed with vitamin C, boosts immunity, while seeds yield oil for cosmetics, and leaves serve as nutritious greens. Bark is woven into ropes, but overharvesting threatens sustainability. Climate change and habitat loss endanger some populations, necessitating conservation through sustainable harvesting and replanting efforts to preserve their legacy.

To grow baobab trees, plant in spring in well-drained, slightly acidic soil, spacing widely for canopy growth. Water sparingly, ensuring winter dormancy, and protect from frost. Mulch to retain moisture, and monitor for fungal issues in humid areas.

Why Baobab Trees Are a Global Treasure

Baobabs are ecological and cultural marvels, with trunks storing up to 30,000 gallons of water to survive arid climates, supporting wildlife from bats to elephants. Their fruit, leaves, seeds, bark, and roots are harvested for nutrition, medicine, and materials, with the nutrient-rich fruit pulp—high in vitamin C and antioxidants—gaining global popularity as a superfood. Growing 20–100 feet tall, baobabs can live over 2,000 years, their hollow trunks serving as shelters, water reservoirs, or even makeshift pubs. Thriving in USDA zones 10b–12, they tolerate extreme heat, drought, and fire, regenerating bark after damage. The Adansonia genus shows striking diversity, with Madagascar’s species adapted to limestone soils and Australia’s to seasonal monsoons. This guide highlights 12 baobab types, including eight species and four regional variants of A. digitata, offering growers a window into their unique traits and potential for ornamental, commercial, or conservation purposes.

1. African Baobab (Adansonia digitata)

African Baobab, the most widespread species, dominates sub-Saharan Africa’s savannas, from Senegal to Ethiopia. Growing 50–82 feet with trunks up to 30 feet in diameter, its cylindrical or fluted trunks store vast water reserves. Its white, nocturnal flowers, pollinated by bats, yield ovoid fruit with powdery pulp used for drinks and superfoods. Leaves, rich in iron, are cooked as vegetables, and bark is woven into ropes. Thriving in sandy, well-drained soils (pH 6–7), it tolerates drought but not frost. Pair with millet or acacia for agroforestry. African Baobab is ideal for African growers or bonsai enthusiasts seeking a multipurpose, iconic tree.

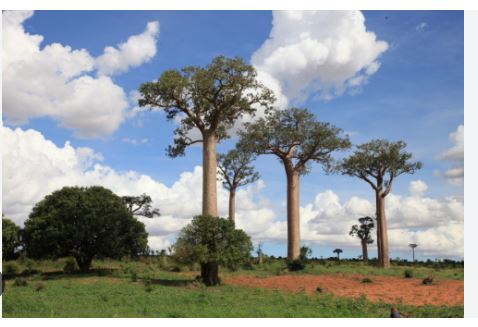

2. Grandidier’s Baobab (Adansonia grandidieri)

Grandidier’s Baobab, Madagascar’s most iconic species, grows 65–100 feet with smooth, cylindrical trunks resembling columns, earning fame in the Avenue of the Baobabs. Endemic to western Madagascar’s dry forests, it produces elongated, reddish-brown fruit with sweet pulp, used for juices. Its leaves are a famine food, and seeds yield oil. Thriving in limestone-rich, well-drained soils, it needs full sun and minimal water. Its endangered status, with fewer than 10,000 mature trees, underscores conservation needs. Grandidier’s Baobab suits tropical growers in frost-free zones wanting a statuesque, rare species.

3. Madagascar Baobab (Adansonia madagascariensis)

Madagascar Baobab, found in northern Madagascar’s dry forests, grows 16–82 feet with irregular, bottle-shaped trunks and reddish bark. Its large, reddish fruit is sweet and pulpy, used locally for food, while leaves treat diabetes in traditional medicine. Pollinated by lemurs and bats, it thrives in sandy or rocky soils with seasonal rains. Its sparse canopy suits wildlife habitats. Plant with vanilla for agroforestry. Madagascar Baobab is perfect for growers in Madagascar or similar climates seeking a versatile, culturally significant tree.

4. Fony Baobab (Adansonia rubrostipa)

Fony Baobab, endemic to western Madagascar, is a smaller species, growing 13–65 feet with swollen, bottle-shaped trunks and warty, reddish-brown bark. Its yellowish fruit, smaller than other species, is used for snacks, and its leaves are medicinal. Thriving in dry, limestone soils, it tolerates drought and needs full sun. Its compact size suits smaller tropical gardens or bonsai cultivation. Pair with aloe for xeriscaping. Fony Baobab is ideal for growers wanting a petite, ornamental baobab with unique bark texture.

5. Za Baobab (Adansonia za)

Za Baobab, widespread in southern Madagascar, grows 33–100 feet with cylindrical or irregular trunks and grayish bark. Its orange-yellow flowers and elongated, dark fruit with tart pulp are used for beverages. Leaves treat respiratory ailments, and seeds yield oil. Thriving in sandy, well-drained soils, it adapts to dry forests or savannas. Its broad canopy supports bird nesting. Plant with sisal for agroforestry. Za Baobab suits growers in tropical zones seeking a productive, resilient species.

6. Suarez Baobab (Adansonia suarezensis)

Suarez Baobab, a critically endangered species from northern Madagascar, grows 65–82 feet with smooth, cylindrical trunks and sparse crowns. Its reddish fruit is eaten locally, and leaves are used for fodder. Pollinated by fruit bats, it thrives in limestone soils with minimal water. With fewer than 1,000 mature trees, conservation is urgent. Its elegant form suits ornamental planting. Suarez Baobab is perfect for growers in frost-free zones wanting to support rare species conservation.

7. Perrier’s Baobab (Adansonia perrieri)

Perrier’s Baobab, the rarest Madagascan species, grows 33–65 feet in northern montane forests, with bottle-shaped trunks and gray bark. Its small, yellowish fruit is less palatable, but leaves are medicinal. Critically endangered, with fewer than 250 mature trees, it thrives in moist, loamy soils, unlike other baobabs. Its dense foliage supports lemur habitats. Perrier’s Baobab is ideal for conservation-focused growers in humid tropical climates wanting to preserve a near-extinct species.

8. Australian Baobab (Adansonia gregorii)

Australian Baobab, or boab, native to northwestern Australia, grows 16–50 feet with bulbous, bottle-shaped trunks and smooth, gray bark. Its white flowers and oval fruit, used by Indigenous peoples for food and medicine, ripen in the dry season. Thriving in sandy, well-drained soils with monsoonal rains, it tolerates fire and drought. Its compact form suits urban or bonsai planting. Pair with eucalyptus for native gardens. Australian Baobab is perfect for Australian growers or tropical gardeners wanting a smaller, resilient species.