Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) is a perennial aquatic plant in the Brassicaceae family, commonly known as the mustard or cabbage family, alongside relatives like broccoli, kale, and radishes. It’s classified under the genus Nasturtium, distinct from the ornamental nasturtium (Tropaeolum), with N. officinale being the primary edible species. As a dicot, it features broad leaves and a creeping growth habit, thriving in water-rich environments. Its taxonomy reflects its peppery flavor, a trait shared with other brassicas.

Watercress is native to Europe and Asia, with its wild origins traced to temperate regions near streams and springs across the Northern Hemisphere. It likely evolved in Western Asia or the Mediterranean, where it grew naturally in shallow, flowing waters. Archaeological evidence suggests its use predates written records, tied to early human foraging in wetland areas. Today, its wild populations persist, though cultivation has expanded its range.

Watercress has a storied past, valued since antiquity for food and medicine. Ancient Persians, Greeks, and Romans consumed it, with Hippocrates reportedly founding a hospital near a watercress-rich spring around 400 BCE for its healing properties. By the 19th century, it became a staple in Victorian England, sold as a street food and cultivated commercially in chalk streams like those in Hampshire. Introduced to North America by European settlers, it’s now grown globally, from the U.S. to New Zealand.

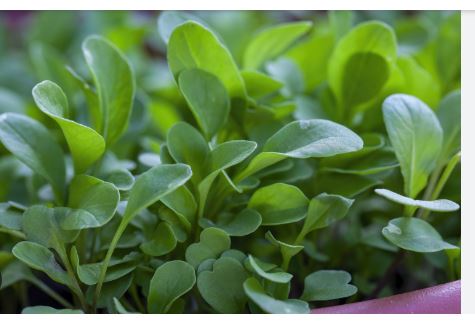

Watercress is easily recognized by its small, round to oval leaves, 1-2 cm wide, arranged alternately along hollow, succulent stems that root at nodes in water. Its dark green foliage contrasts with tiny, white, four-petaled flowers that bloom in clusters during summer. The plant grows 10-50 cm long, often floating or sprawling across water surfaces. Its sharp, peppery scent and taste—due to glucosinolates—set it apart from lookalikes like fool’s watercress (Apium nodiflorum).

Watercress is a cool-season crop, thriving in spring and fall when temperatures range from 50-70°F (10-21°C). In temperate regions, it’s harvested from March to June and September to November, though year-round production occurs in controlled environments like hydroponic systems. Wild watercress peaks in spring, while cultivated supplies from Europe, the U.S., and Asia ensure availability in markets most of the year, often sold fresh in bunches or bags.

Watercress adds a bold, peppery kick to dishes, making it a versatile green. It’s commonly eaten raw in salads, paired with milder greens or fruits like pear to balance its bite, or layered in sandwiches (e.g., classic British watercress tea sandwiches). Cooked, it wilts into soups (e.g., watercress soup with potato), stir-fries, or pestos, retaining its zesty flavor. It also garnishes meats or blends into sauces, offering both taste and visual appeal.

Watercress is a nutritional powerhouse, low in calories (11 kcal per 100 g) yet rich in vitamins and minerals. It’s an exceptional source of vitamin K (250 µg per 100 g, over 200% DV), vital for bone health, and vitamin C (43 mg, 48% DV), boosting immunity. It provides antioxidants like beta-carotene and glucosinolates, linked to cancer prevention, plus calcium, iron, and folate. Its high water content (95%) aids hydration, making it a dense, nutrient-packed green.

Cultivation of Watercress

Climate Requirements

Watercress thrives in cool, temperate climates with temperatures between 50-70°F (10-21°C), ideal for vigorous growth. It tolerates light frost but suffers above 80°F (27°C), where it may bolt or lose flavor. Partial shade is preferred in warmer regions to prevent overheating, while consistent moisture mimics its natural stream habitat.

Water Requirements

As an aquatic plant, watercress demands clean, flowing water with a pH of 6.5-7.5. It grows best submerged in 1-2 inches (2.5-5 cm) of slow-moving water or in saturated soil. Spring water or filtered sources are ideal, as stagnant or polluted water invites disease and stunts growth; oxygenation is key.

Soil Preferences (for Non-Aquatic Beds)

In non-submerged setups, watercress prefers rich, organic soil—loamy or peaty—with high water retention. A mix of compost and sand ensures drainage while keeping roots moist. Soil beds must stay waterlogged, often achieved with shallow trenches or gravel layers to maintain saturation.

Site Selection

Choose a location with access to shallow, running water (natural streams, springs, or artificial channels) or a low-lying, shaded spot for soil beds. Avoid full sun in hot climates—4-6 hours of filtered light works best. Proximity to a clean water source is critical, as is protection from strong winds or flooding.

Propagation Methods

Watercress is propagated via stem cuttings (4-6 inches) from healthy plants, rooted in water or wet soil within days, or by seeds sown shallowly in moist media. Cuttings are faster and preserve flavor traits, while seeds (germinating in 7-14 days) suit larger-scale planting but require consistent dampness.

Planting Time

Plant in early spring (March-April) or fall (September-October) in temperate zones for optimal growth; year-round cultivation is possible in mild climates or greenhouses. Start cuttings or seeds when water temperatures reach 50°F (10°C), ensuring a cool, stable environment for rooting.

Water Management

Maintain a steady flow of water at 1-2 gallons per minute in channels, or keep soil beds saturated with daily irrigation if not submerged. Avoid standing water—circulation prevents algae and rot. In hydroponic systems, nutrient-rich water cycles continuously, mimicking natural springs.

Fertilization

Watercress needs minimal feeding in nutrient-rich water; in soil or hydroponics, apply a diluted liquid fertilizer (e.g., 10-10-10 NPK) every 2-4 weeks. Organic options like compost tea or fish emulsion enhance growth without overpowering its natural flavor. Avoid excess nitrogen, which promotes leafiness over quality.

Spacing and Support

Space plants 6-12 inches apart in water beds or soil rows to allow spreading and air flow. No trellising is needed—stems float or creep naturally. In dense setups, thin seedlings to prevent overcrowding, which can trap moisture and invite fungal issues.

Pest and Disease Management

Aphids, water snails, and leafhoppers are common pests—control with insecticidal soap or natural predators like ladybugs. Diseases like downy mildew or root rot arise in poor water quality; ensure clean, aerated conditions and remove affected plants promptly. Wild harvesting risks contamination (e.g., liver flukes), so cultivated sources are safer.

Growth Cycle

From planting, watercress is harvest-ready in 4-7 weeks, with continuous cropping possible as it regrows from cut stems. It’s a perennial in mild climates, producing for years if maintained, though annual replanting refreshes vigor in commercial setups. Flowering (summer) signals a flavor shift—harvest before if pepperiness is desired.

Harvesting

Cut stems 4-6 inches long above the waterline or soil when leaves are dark green and tender, typically 2-3 inches tall. Use scissors to avoid uprooting; harvest regularly to encourage regrowth. Pick in the morning for peak freshness, rinsing immediately to remove debris or pests.

Post-Harvest Care

Store fresh watercress in a refrigerator at 32-36°F (0-2°C) with stems in water or wrapped in damp cloth, lasting 1-2 weeks. Avoid prolonged storage—flavor fades quickly. For cultivation, trim beds post-harvest, clear dead growth, and refresh water to sustain perennial plants or prep for replanting.